Philippe Mores, Counsellor at the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs of Luxembourg, is currently attending the Oxford Impact Investing Programme 2020 thanks to an InFiNe.lu scholarship. Read here the outcomes of what he is currently learning.

The Oxford Impact Investing Programme has selected a total of 60 students from all over the world with different, but related stakeholder profiles from the impact investing sector. These include primarily the financial sector, investment banking, non-profit, financial/insurance or philanthropy backgrounds, but also others such as public service, higher education or pharmaceuticals, while gender parity is being respected. The objective of the course is to give the participants tools, structures and ideas that can be applied in their day-to-day work. The programme addresses the question how impact investing can make a difference in tackling issues and inequalities despite – or especially – in times of crisis. Renowned professors, academics as well as professionals, CEO’s and distinguished leaders in the field are sharing their experiences and the Executive Programme is built around four pillars: Inspiration and ideas, Theory and substance, Application of knowledge and Action-oriented engagement.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this year’s Executive Programme is structured differently to the previous ones. The course is being held online, with substantial sessions or classes twice a week, besides additional live presentations on specific topics, individual tutorials, one-on-one coaching sessions and access to a virtual library of articles, books and other material is provided. The Programme also manages to include numerous networking possibilities to get to know and exchange with peers and professors alike.

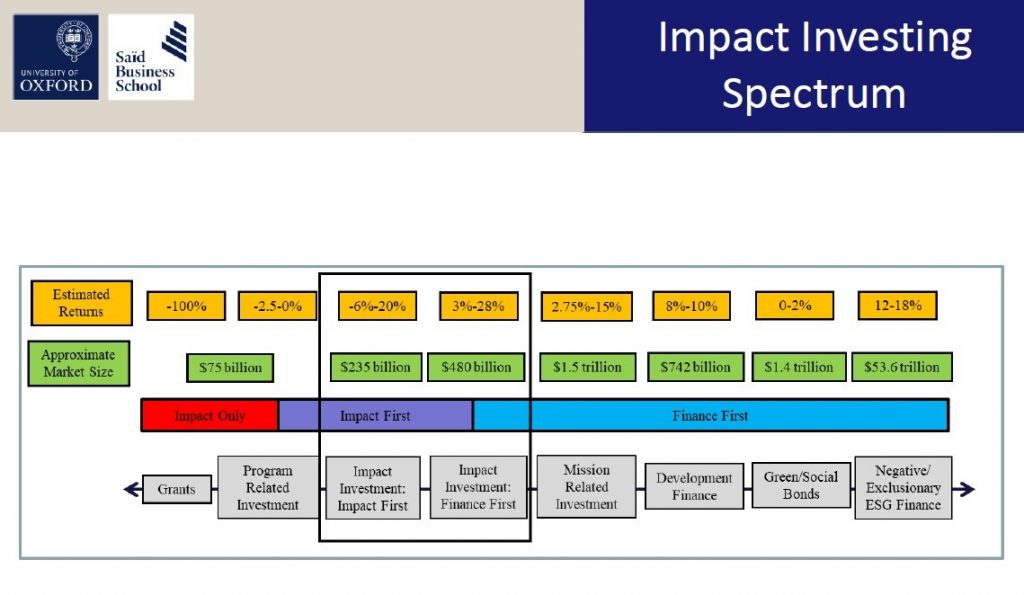

The first week has dealt with different aspects of impact investing (the impact finance spectrum), financial parameters, key frameworks, ideas and suggestions. Definitions may vary but in essence, impact investing intends to create a positive, additional impact beyond purely financial returns.

With a transfer of some 58.7 trillion USD of wealth in the next 35 years, the potential for transformational change is huge. New markets will emerge in the fields of community development, microfinance, small business finance, education, renewables, sustainable agriculture, health and wellness, natural resources conservation and sustainable consumer products and fair trade – all in the overall context of the 17 SDGs.

During the first session, focus was put on so-called “wicked problems” (such as human environmental damage, climate change, infectious diseases, loss of biodiversity, digital power and inequality, political unrest) which are paramount, but difficult to address. They are ambiguous and unique, hard to define, seemingly limitless and often a symptom of another problem. Facts and figures matter to solve them but so do the narratives to overcome these challenges. Yet, problem-solvers are also liable for consequences of actions. Tools such the Human Security Index in the context of the SDGs can provide a frame but it still takes deliberate leadership, a moral compass and a theory of change to aim for a solution. Strategic learning is key for a business to reflect on values and assumptions, stakeholder experience and investment results. Planned results may vary from actual results achieved but should still lead to unanticipated opportunities rather than unanticipated threats.

At the end, the class discussed the Ghana Afram Plains case study (whether or not to invest into the project to reduce hunger, create jobs and economic opportunities for 80,000 smallholder farmers) in smaller but also in bigger groups of people to illustrate different aspects, interests and point of views of the scenario.

Personal reading suggestions (out of many others):

The second and current week has so far been focusing on impact measurement and management. These are essential because they allow to demonstrate and make the case for impact investing, general claims will likely not convince (traditional) investors to change their behaviour and strategy. Whereas measurement of results as such has always been conducted i.e. through cost/benefit analyses, its scope has been somewhat limited. Last Tuesday’s session used several live polls, to be completed by the class during the session, to discuss assumptions from different stakeholders but also trends in impact measurement. Impact measurement and management need to illustrate “material” social or environmental change that is preferably positive but any potential negative externalities should also be taken into account to address or try to mitigate them. The class discussed a full range of different reporting methodologies, ESG and CSR that exist nowadays and regulators are getting increasingly involved too (carbon taxation, EU regulations and directives). Lately, new hybrid value creation models are being used to assess public management contracts. Whereas the fundamental questions remain valid (what to measure, who to measure, how much to measure, its contribution and its risks) to do no harm, benefit people and planet and contribute to solutions, IRIS+, IFSR or the IFC principles focus more and more on the day-to-day management of impact, not just solely its measurement. Outputs created need to be linked to longer-term outcomes and complement those with additional measures, if possible. Should detailed metrics be pre-defined and to what extent or should principles of measurement provide for a more coherent, overall guidance?

Finally, the COVID-19 “factor” was discussed as well since it accelerates specific vulnerabilities with primary but also a full range of secondary effects. To what extent the COVID-19 factor should be used more horizontally in measurement provoked a discussion that is yet to be fully assessed. A lively debate also focused around who determines the measurement parameters and who they should be focused on. Are the indicators defined by the source of the investment or by the stakeholders or the final beneficiaries? Are these indicators always aligned? In the end, whereas measurement and management are essential, they also have their limits; for example, Co2 emissions are going up drastically and while many reports prove this, this has so far not resulted in a more consequent investment to mitigate their effects.

Personal reading suggestions:

Apart from the courses and individual sessions, the class has also been divided up in smaller, permanent groups of students in which additional exercises (group exercises and individual exercises) are being discussed. For instance, throughout the Programme our group will have to develop the case of a Head of sustainable investing at a European Private Bank and develop a strategy and a concrete plan to mobilise £100m to get the bank involved in SDG14 investing. The results will be presented and challenged by the class at the end of the Programme.

Author: Philippe Mores

InFiNe is the Luxembourg platform that brings together public, private and civil society actors involved in inclusive finance. The value of InFiNe lies in the wide range of expertise characterised by the diversity of its members.

With the support of

Inclusive Finance Network Luxembourg

39, rue Glesener

L-1631 Luxembourg

G.-D. de Luxembourg

Tel: +352 28 37 15 09

contact@infine.lu

R.C.S. : F 9956

Legal notice

Privacy notice

Picture 1 © Pallab Seth